It was President Richard Nixon’s decision, which he announced on August 8, 1974, to leave office. But he had little choice. There was near-total agreement in both parties that he had committed some (or all) of what he was accused of: abuse of power, obstruction of justice, and contempt of Congress.

Fifty years later, would the same thing happen in today’s political climate?

“I really find it hard to believe that Nixon would’ve resigned in an environment like the one we have today,” said Brian Rosenwald. As a lecturer about conservative politics at the University of Pennsylvania, Rosenwald has thought about the what-ifs of the Watergate scandal. Nixon, he said, “would have dug in. He would have had enough support to avoid conviction”.

Up until the very end, Nixon was dug in. The day before he relented, the front page of the Washington Post read, “Nixon Says He Won’t Resign.”

But unlike what we might expect today, Nixon’s party had abandoned him. On August 7, 1974, Senator Barry Goldwater (who had been the last GOP presidential nominee before Nixon) and Republican leaders in Congress visited the White House. Goldwater told reporters outside, “Whatever decision he makes, it will be in the best interests of our country. … There’s been no decision made. We were merely there to offer what we see as the condition on both floors.”

The condition was dire. Republican Congressman John Rhodes said, “Impeachment is really a foregone conclusion.”

AP Photo

The majority of Republicans were likely to vote to impeach Nixon in the House, and there weren’t enough Republican Senators to block his conviction in the Senate.

A day after the meeting, Nixon’s decision led to the iconic Washington Post headline: “Nixon Resigns.”

In the fifty years since that announcement, that White House visit by leaders of the president’s own party telling him his time was over may tell us less about what was happening then, then it tells us about what is happening in our politics now.

“In our modern era, where we’re so cynical about our politics, it’s almost impossible to capture how different the political landscape was in ’72, ’73, ’74,” said Garrett Graff, the author of “Watergate: A New History.” “Even Democrats trust Nixon, because they say, ‘The President would never lie to the American people. We can’t impeach the President. He’s the President! If he is saying he’s not involved in Watergate, he’s telling us the truth.'”

Simon & Schuster

For in August 1973, Nixon told the American people, “I had no prior knowledge of the Watergate break-in.”

No prior knowledge, perhaps … but Nixon had been involved in the cover-up after the burglary and wiretapping of the Democratic National Committee Headquarters, abusing his powers to obstruct the investigation, and defying Congressional subpoenas for evidence.

Proof came from one of the bombshell moments in the Senate Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities’ Watergate hearings, when it was revealed by former Nixon aide Alexander Butterfield that there were recording devices in the Oval Office. On one of the tapes: direct evidence against the president.

Graff said, “What comes out is this ‘smoking pistol’ tape, from June 23, 1972, in which Nixon is heard saying, ‘They should call the FBI in and say that we wish for the country, don’t go any further into this case, period.’ It is a recording from the first day that Richard Nixon is back in the White House after the Watergate break-in. And it effectively shows that Nixon was part of the cover-up from the earliest hours.

“Watergate is a story of incredible corruption and criminality,” Graff said. “But to me, it’s actually an incredibly inspirational story of how our system works, and the incredible ballet of checks and balances written into our Constitution. Every institution in Washington had to come together to play a special, and important, and unique role.”

Asked what was a basic shared norm that they believed in in 1974, Graff replied, “Everyone agreed, at that moment, Richard Nixon was not above the law.”

That agreement could be reached because politicians weren’t attached to their parties the way they are today.

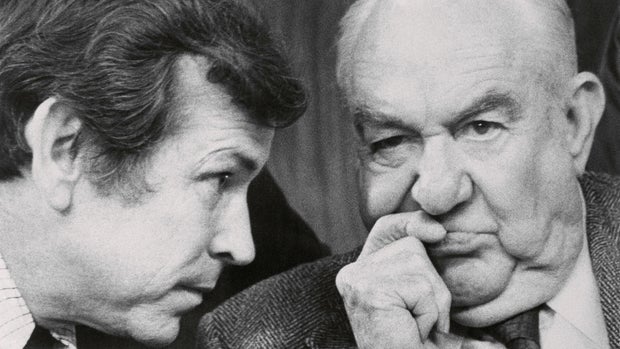

Sen. Howard Baker of Tennessee, the top Republican on the Watergate committee, probed for the truth. He didn’t erect obstacles to protect his party’s president, famously asking, “What did the president know and when did he first know it?”

Bettmann via Getty Images

Rosenwald said, “Our electoral politics have changed. In the last half-century we’ve become much more geographically polarized, which means red states and blue states. And the way that manifests today is the most important election for most people are primaries, because that’s the place they can lose. And who shows up for primaries? It is the people consuming ideological media. They’re engaged, and they’re usually far right or far left.”

In Nixon’s day, lawmakers answered to an electorate where voters consumed the same information. Eighty-five percent of U.S. households watched some portion of the Watergate hearings, which featured White House counsel John Dean exclaiming, “I began by telling the president that there was a cancer growing on the presidency.”

“Nixon didn’t think that he was committing crime,” said Graff. “He thought he was the law-and-order president.”

Nixon may have believed it, but there was no pro-Nixon media apparatus to feed that alternative reality to the public during the 784 days between break-in and resignation.

“I don’t think we could see a moment like that happen [today],” Graff said, “because of the media environment. The poisoned information ecosystem that politics now exists in is all but inescapable. If Richard Nixon had Fox News in 1974, he would’ve survived.”

Rosenwald imagines how the political and media developments of our world today would have played out 50 years ago, in response to a “smoking gun” White House tape: “They would’ve said, ‘They’re just getting rid of our guys. They’re getting rid of our champions.’ They would have pointed at all kinds of malfeasance from Democrats and said, ‘Oh, look at those guys still serving, nobody ran them out of office.’ And they would’ve pointed at the media and said, ‘And they did nothing about it. They are out to get you. They hate you.’ And then basically said, ‘Whose side are you on? Are you on the side of your enemy, or are you on the side of your guys?’ Nixon might not be perfect but all of a sudden he’s ‘our guy.'”

“He’s our guy” may capture best the modern instances where lawmakers put party above all else. Though that instinct did not prevail when Democratic leaders convinced Joe Biden to abandon his campaign, it did rule with Donald Trump, when the moral stakes were at Watergate levels.

Just days after the January 6th attack on the Capitol, Republican leaders accused the president of their party of breaking his oath. In a recording made public a year later, House Speaker Kevin McCarthy spoke to his colleague, Republican Congresswoman Liz Cheney, about an impeachment resolution, telling her, “The only discussion I would have with [Trump] is that I think this will pass, and it would be my recommendation you should resign.” And on February 13 [after Trump had already left office], Minority Leader Mitch McConnell told the Senate, “There is no question, none, that President Trump is practically and morally responsible for provoking the events of that day.”

But in the end, there was no White House visit from leaders in Trump’s party. And in 2024, McCarthy has endorsed Trump for president, as McConnell has.

Fifty years after Watergate, the question is not whether a tough-love visit by members of a president’s party is possible. It is. What’s changed is what motivates the lawmakers willing to take the walk.

For more info:

Story produced by Reid Orvedahl. Editor: Ed Givnish.